Economics

New Zealand Eyes Sweden as Roadmap for Negative Interest Rates

By Matthew BrockettSeptember 9, 2020, 7:00 AM GMT+10 Updated on

- RBNZ studies other central banks as it readies new stimulus

- Former Riksbank deputy says sub-zero rates worked well

LISTEN TO ARTICLE

4:32

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

In this article

EUREuro Spot1.1810EUR+0.0007+0.0593%1006035ZACCIDENT COMPENSATION CORPPrivate Company

As New Zealand’s central bank prepares plans for taking interest rates negative to support its recession-hit economy, Sweden’s experience is emerging as the most relevant guide.

The Reserve Bank is studying the other countries that have employed negative rates and the Scandinavian kingdom — a small, open economy like New Zealand — is drawing particular attention. Sweden’s Riksbank imposed negative rates for five years to head off the threat of deflation.

The controversial monetary policy tool has been used by only a handful of central banks in Europe and Japan. Australia’s Reserve Bank is cool on the idea, but there is renewed interest internationally as policy makers seek new ways to bolster their virus-battered economies.

Negative rates were successful in Sweden because they achieved the aim of returning inflation to target without causing any significant distortions in the economy, said Lars Svensson, an economics professor in Stockholm and a former deputy governor at the Riksbank.

“The short answer is that negative rates worked well, in that the pass-through to market interest rates was over time almost one-to-one,” Svensson said in an emailed response to questions. “I agree with the assessment of our supervisory authority that the risks to financial stability associated with household indebtedness are relatively small.”

RBNZ Governor Adrian Orr has warned of the dangers posed by “low inflation or deflation” and expressed a preference for a negative official cash rate combined with loans to banks to get borrowing costs lower if required. The aim would be to push wholesale rates negative, dragging retail rates closer to zero and thereby stimulating greater demand for debt.

Some New Zealand wholesale rates fell below zero for the first time on Wednesday as investors increased bets on a negative policy rate. Two and three-year swap rates sank to minus 0.005%, as did the yield on the benchmark three-year bond.

Most economists expect the RBNZ to cut its cash rate from 0.25% to minus 0.25% or minus 0.5% in April next year, and some see the chance of an earlier move. Orr is expected to provide an update on the RBNZ’s plans in his Monetary Policy Statement in November.

The RBNZ said it’s in constant communication with other central banks as it prepares a package of additional stimulus measures and declined to comment further.

The Swedish Experience

On the opposite side of the globe, Sweden provides a roadmap for what may be in store. There are some obvious similarities between the two export-reliant nations. Both have small populations — about 10 million in Sweden and 5 million in New Zealand — and currencies that are among the 10 most-traded in the world.

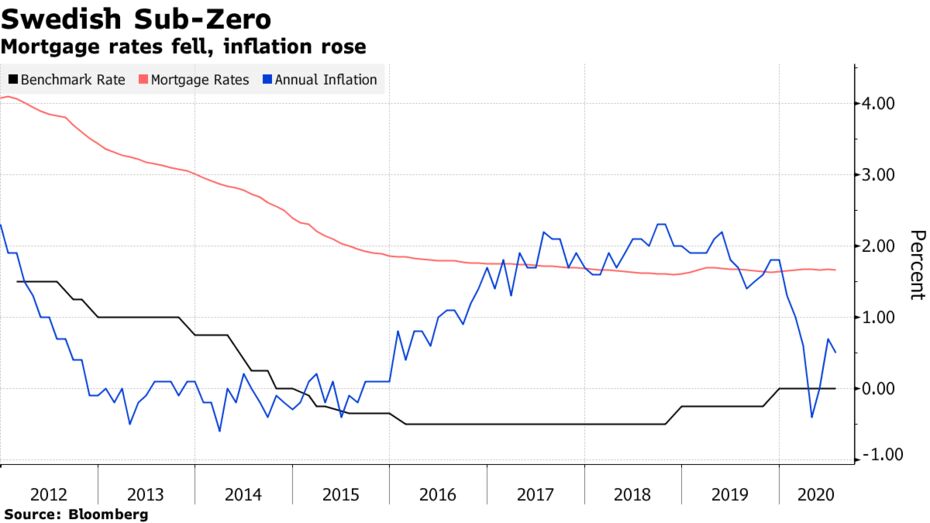

The Riksbank sent its policy rate into negative territory in early 2015, reaching a low of minus 0.5% before raising it back to zero late last year.

Swedish mortgage rates dropped below 2%, causing house prices to surge to double-digit annual gains, but unemployment fell and the economy grew. Crucially, headline inflation rose steadily from minus 0.4% in mid-2015 to meet the central bank’s 2% target two years later. Inflation expectations also rose.

While central banks in Denmark, Switzerland, the euro area and Japan are all using negative interest rates, the policy isn’t without side effects. Very low rates squeeze lending margins, reducing profitability for banks, and can pose threats to financial stability by incentivising riskier investments.

In Sweden, the subzero-regime was advantageous for borrowers but brutal for the country’s pension industry, which struggled to generate the returns needed when bond yields turned negative.

‘Risky Experiment’

That could also become an issue for New Zealand entities, such as the government-owned insurer Accident Compensation Corp., which need to generate returns on pooled funds to cover future claims, said Jarrod Kerr, chief economist at Kiwibank in Auckland.

“The economy is simply not in a bad enough place to justify the risky experiment that is negative rates,” said Kerr. “The distortions thrown up by negative rates more than offset the stimulatory benefit.”

Svensson said negative rates weren’t without controversy in Sweden. There was “quite a bit of misleading and unsubstantiated criticism” of the policy setting, including gripes about a weaker currency that made trips abroad more expensive.

“Critics were upset by the weak krona, not understanding that the weak krona was an inherent part of the transmission of expansionary monetary policy,” he said.

The prospect of negative rates in New Zealand has kept a lid on its currency in recent months. The kiwi dollar is up about 16% against the weaker greenback since its March low compared with almost 26% for the Aussie dollar.